The first perfect computer

This is a story about restoring and upgrading a Commodore Amiga 1000, the first model of the Amiga series.

Many of you might be familiar with the popular Amiga 500 or later models, but the Commodore Amiga 1000 was actually the first model of the Amiga series produced.

I consider the A1000 a significant piece of home computing history. Arguably one of the most important machines of the 16-bit revolution period, considered by many to be the first multimedia computer, it marked the beginning of Commodore’s last cycle, after the huge success of the C64, in the history of personal computing.

If you think Steve Jobs invented pompous computer launch events, check out The World Premiere of the Amiga, a black-tie event held at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City on July 23rd, 1985.

I never owned an A1000. I was still happily exploring and playing with my C64 when it came out. However, I remember drooling over one at the local computer store in Aveiro on my way home from high school, where I regularly began camping. I remember reading about it in computer magazines, and I have a very vivid memory of seeing one at a fair in a booth playing the infamous NewTek Demo Reel 1 at the sound of the Art of Noise Paranoimia song.

Later, the more affordable Amiga 500 came out. I had some money put aside from summer jobs, and on a trip to Andorra, I saw one for sale in a shop. My parents chipped in the rest and helped me buy it. That was my first Amiga, a second-hand smuggled-in A500 with a Spanish keyboard layout. I’ll never forget that useless Ñ key.

I had to live with the Ñ key for some years

I had to live with the Ñ key for some years

I had a few Amigas after that over the years, A500, A3000, A600 and A1200, but none of them compared to the Amiga 1000 in first impact, personality and beauty, not even the A3000. Having spent quite a big part of my early computing days playing and working with Amigas, to the point of calling it a religious obsession, it always felt wrong that I never owned one.

That was solved recently when I bought an Amiga 1000 on eBay. This is the long-overdue story about how I restored, fixed, and upgraded it and my future plans. If you’re the rabbit hole type, I added as many links and references as I could so you can dive deeper into the Amiga world. I hope you enjoy reading it.

My Amiga 1000 arrives in the mail

My Amiga 1000 arrives in the mail

Unpacking and first tests

I got the machine from Germany, as-was, untested, and with no keyboard (later, I bought a keyboard from another deal). The whole thing cost me around 400 euros, a bargain considering other A1000 deals out there now, but there was a good chance that it had hardware issues, which I’d be OK with; they’d be within the scope of my restoration plan.

Who is Franz Barta??

Who is Franz Barta??

The first thing that caught my attention was the label, which read “Eigentümer (owner): Franz Barta”. If I had to guess, this Amiga belonged to some organization, maybe a school or a company, and the computer was assigned to Franz. I tried using my Google-fu to learn more about Franz Barta but had no luck.

My Amiga 1000 serial number

My Amiga 1000 serial number

My model is a PAL Amiga 1000 with the serial number XM4056969NP, made in Japan. This level of detail may seem irrelevant, but it’s not. The Amiga 1000 has a few variants and revisions; funny enough, their differences are important to retro-enthusiasts today. I’ll explain.

Back in the day, computers would typically connect to TV sets or dedicated monitors using either modulated RF, composite (sometimes with separate chroma/luma, also known as S-Video), or RGB video and encode the signals using either NTSC in the US and some Americas, PAL or PAL/SECAM in the rest of the world. These video standards are derived from the country’s electrical power frequencies. The US uses 110V at 60Hz, NTSC video runs at 30 frames per second, while most of the world uses 220V at 50Hz and PAL at 25 frames per second.

World map distribution of PAL vs NTSC, by Wikipedia

World map distribution of PAL vs NTSC, by Wikipedia

You see what’s going on here? Many pieces of equipment of this time used the mains electricity frequency to generate internal clocks, usually the video-related ones, and the Amiga computer was no exception to this rule. If you bought an Amiga in the US and brought it to Europe, it wouldn’t work correctly, and vice versa. It also means that we had games or versions of the same game made explicitly for PAL or NTSC, and you needed the correct version to play it correctly.

If this topic interests you, check out this in-depth PAL VS NTSC - The You’re Not Stupid Guide video.

But there’s another different thing. NTSC A1000s have two boards, not one: the motherboard and a daughterboard, also known as WCS (Writable Control Store). Why? Funny story. When the Amiga 1000 was announced and launched, the boot ROM, also known as Kickstart, wasn’t ready yet. Commodore was under a lot of pressure and didn’t want to wait, so they added this second board WCS on top of the main board as a hack to allow loading the boot ROM from a floppy disk. The PAL Amiga 1000 model came later, they also required loading Kickstart from floppy, official ROM chips never materialized on the A1000, but at least now the WCS logic was part of the motherboard.

An NTSC Amiga 1000 motherboard with the WCS daughterboard

An NTSC Amiga 1000 motherboard with the WCS daughterboard

In fact the Amiga 1000 had a few board revisions after launch. Look at this delicious note from Amiga Engineering in ‘86:

A note from Amiga Engineering to Hardware Developers

A note from Amiga Engineering to Hardware Developers

This matters for retro enthusiasts because there is a third-party board called Rejuvenator, a modernized version of the older Phoenix board, that you can buy or build. It upgrades the Amiga 1000 to a full ECS Amiga with 1Mb or 2Mb of Chip RAM by replacing the WCS daughterboard.

This board is only compatible with NTSC Amiga 1000s, so unless you have one of those very rare PAL Amiga 1000s with the WCS daughterboard, you’re out of luck.

Doesn’t matter. I’m in Portugal, so I bought a PAL Amiga 1000. Later I found other ways to upgrade it.

When I powered on the A1000 for the first time, I wasn’t expecting much. I could hear the PSU fan, and the power LED lit up, but the screen was black, and nothing happened. That’s OK, I thought; this is a restoration project; I’ll figure it out.

I opened the Amiga and noticed a few things. The first was the famous signatures from the team that designed it etched on the inside of the case.

Inside of the Amiga 1000 case

Inside of the Amiga 1000 case

That’s Jay Miner’s signature on top right corner, considered the father of the Amiga, and Mitchy’s, his dog’s, paw.

The second thing I noticed was that my Amiga had another board on the motherboard, which was a surprise. “This is a PAL Amiga, so this can’t be the WCS,” I thought. It wasn’t.

This Amiga was fitted with a third-party board that appeared to be a brand-less, “Made in Germany” clone of the Spirit Inboard fast RAM expansion that plugs on top of the MC68000 CPU socket. After much searching online, I finally found it. The 32x 41256P DRAM chips gave it away; the board is a FutureVision 4 MB expansion.

FutureVision 4 MB RAM expansion

FutureVision 4 MB RAM expansion

I take it off the motherboard, though, as I don’t have the use for it; I have other plans to add fast RAM later. The Amiga still doesn’t boot, so it’s time to disassemble everything and troubleshoot. The board is gorgeously clean, with no signs of corrosion or damage, which is good news.

The guts of my non-working A1000 without the FutureVision expansion

The guts of my non-working A1000 without the FutureVision expansion

Recapping everything

The first thing that comes to every retro-enthusiast’s mind when a machine isn’t working is replacing its capacitors—recapping, as it’s called. Electrolytic capacitors have a limited lifespan and tend to leak or dry out over time, causing all sorts of issues to old computers. I don’t see any leakage, but maybe this will help solve the problem. Either way, it’s always good practice to do it. So, I ordered a complete set of capacitors from Mouser Electronics, armed myself with my Hakko FR-301 desoldering gun, and started the job.

I replace both the motherboard and the PSU capacitors. Some of them don’t quite fit the holes because either the specs aren’t 100% exact (you can typically use equivalents if you respect the minimum voltage and tolerance), or, guess what, capacitors with the same specs have better quality and are smaller now. So I must bend the legs a bit, but it’s all good.

Motherboard with new capacitors

Motherboard with new capacitors

Replacing the PSU capacitors too; some are quite big

Replacing the PSU capacitors too; some are quite big

The PSU fan makes an annoying noise. I opened it up and oiled the fan bearing. It’s a bit better now, but it won’t last; I’ll have to replace it someday.

I turn on the computer again, and nothing smells funny, which is always a good sign, but it still isn’t showing any image or booting. It’s time to get my hands dirtier.

New chips and a PiStorm experiment

I grab the oscilloscope and multimeter and start testing the signals. The great thing about computers from this era is that they all provided schematics and service manuals. The power rails are good, the PSU sends the correct voltages, and the clock signal is there. It’s not that.

Testing the signals on the PCB

Testing the signals on the PCB

It’s time for the next trick in the bag: replacing chips and seeing what happens. Thankfully, all the big chips are socketed, so it’s easy to replace them. I have an old Original Chip Set OCS Amiga 500 lying around, so I grab the CIA chips, Paula, Denise, and even the MC68000 CPU and start swapping them. Sadly, I can’t replace Agnus because the Amiga 500 uses the FAT version, not the DIP that the Amiga 1000 uses.

No luck, though. The Amiga still doesn’t boot. Now I’m getting desperate. What can possibly be wrong?

I had an idea. There’s an open-source project called PiStorm that essentially replaces your Amiga’s CPU with a Raspberry Pi. You literally remove the MC68000 CPU, plug in the PiStorm with Raspberry Pi in the same socket, and boot your Amiga. The software running in the Pi then emulates the MC68000 CPU, and because it has access to all of the addressable memory, it can even emulate memory and peripherals, like fast RAM, the keyboard and mouse, networking, etc.

Side note: The Amigas all have two types of RAM: chip and fast. The Agnus chip controls the chip RAM, which is shared with the video and audio hardware, and the CPU controls fast RAM. You can expand any Amiga with more Fast RAM but can’t extend the chip RAM beyond what the Agnus can address. One of the significant limitations of the Amiga 1000, which will stop you from running some games and software with higher requirements, is that its first-generation Agnus can’t address more than 512Kb of chip RAM.

Anyway, back to the PiStorm. I don’t want to use emulation with this Amiga; it’s cheating. But to troubleshoot what’s going on, this might be a good idea because the PiStorm takes over a lot of core subsystems. I order the basic PiStorm from AMIGAstore. They don’t mention the Amiga 1000, but I know it works from reading in the forums.

PiStorm and Raspberry Pi replacing the CPU

PiStorm and Raspberry Pi replacing the CPU

I found a Raspberry Pi Model 3A+, downloaded and installed the software, and tweaked the configuration. Instead of trying to boot with Kickstart and Workbench, I will use a diagnostic ROM. DiagROM tries to boot the computer using as little hardware as possible and presents you with a menu where you can perform tests on multiple systems and peripherals. Let’s try to boot now.

BAM, it boots! I have video, success. The keyboard and mouse work too. Let’s do more tests. Surely something will fail and I will be able to pinpoint the issue.

But nothing fails. RAM tests pass, sound is fine, video is fine, and so on. What the flip? Alright, let’s try to boot Kickstart and Workbench out of the PiStorm while at it.

Workbench booting off the PiStorm on the Amiga 1000

Workbench booting off the PiStorm on the Amiga 1000

It boots. Everything works. I can run games and apps. Seriously?

Why doesn’t it work without the PiStorm? I couldn’t figure it out. Then, I started exchanging emails with David Dunklee, the author of a modern Amiga 1000 expansion board called Parceiro, which I will discuss later in this blog post. David was unbelievably patient and helpful. He sent me multiple emails with tips and detailed step-by-step instructions on what to test and how to do it.

And then, a few days later, something magical happened. David sent this email, which I think he won’t mind me sharing:

This is basically describing my setup: an A1000 PAL with an old German memory expansion in the CPU socket. Could there have been a bigger coincidence?

Alright, let’s replace the CPU socket on the PCB with a new one. I boot the computer again, now without the PiStorm, and voilá. A few seconds after powering up, I hear the infamous floppy drive click sounds and the Kickstart screen appears. The Amiga 1000 is alive and well.

Kickstart boot screen

Kickstart boot screen

David was right. I had a loose CPU socket from the heavy FutureVision expansion board sitting there for years. The PiStorm worked because it uses round pins, which apply more pressure in the socket holes, making a better connection. Pure luck.

Here’s a pro tip: replace all the DIP sockets in your old computer with new ones with machined round contacts. Old dual-wipe contact sockets are crap and the source of many issues with retro-computers. This was an extreme case, but it’s frequent to have to press chips down to make contact with old computers.

PiStorm round pins connector

PiStorm round pins connector

I have a working Amiga 1000 now. It’s time to load some games and software and enjoy it. But how? I don’t have a hard disk or many floppy disks from the past; all the software is online now.

Parceiro

I mentioned David Dunklee and the Parceiro board above but didn’t give much context.

Parceiro (which, by the way, means “Partner” in Portuguese) is an A1000 external expansion that packs an AUTOBOOT SD Card Reader, 8Mb of AUTOCONFIG fast RAM, a battery-backed real-time clock, and three banks of user-flashable Kickstart-in-ROM, all in one small and sleek package that plugs into the 86-pin expansion port.

I found out about the Parceiro 2 when I read a thread in the AmigaLove forum called “The Best Amiga 1000 Upgrade in 30 Years: Parceiro II” (video), and I didn’t think twice; I had to have one.

This project is a personal hobby and work of passion from Mr. David Dunklee; it deliberately doesn’t have a website, and you can’t find it in retro computing stores either. If you want one, you have to get someone who already owns one to give you David’s contact information and then email him, which I did. I got a reply a few days later and entered a waiting list. David doesn’t stock Parceiro or outsource manufacturing either; he builds them on demand with his bare hands; even the case seems to be 3D printed on a high-quality SLA printer, so you have to wait a bit.

A few weeks later, David emailed me to say my Parceiro was ready. I Paypal’d him the agreed amount, and a few days later, I had it in my hands.

When the Parceiro arrived, I was still in the middle of troubleshooting why my Amiga 1000 wasn’t booting, and plugging in the Parceiro didn’t change its condition. What changed, though, was that David is incredible, has a fantastic knowledge of the Amiga electronics, and started helping me fix mine. We exchanged over 20 emails back and forth, sometimes more than one a day. David would send me highly detailed instructions on what to try, what to measure with the oscilloscope, what to replace, manuals, schematics, and so on. He was incredibly patient and helpful, beyond what I’d expected, and I’m very grateful for that.

We kept in touch.

Later, David offered a trade-up/trade-in deal for an upgraded version that doesn’t require soldering on the motherboard (the first one required changing two GAL chips and a few wires). Also, this new version comes with an accelerator, which is basically a drop-in replacement of the 680000 CPU, an MC68SEC000 in a QFP package running at 28MHz. It makes the Amiga around 4 times faster, which is a lot.

I obviously took the offer.

The Parceiro II+ Accelerator board

The Parceiro II+ Accelerator board

It's a simple drop-in replacement that fits the 68K socket

It's a simple drop-in replacement that fits the 68K socket

So, I now have a fully working Amiga 1000, accelerated at 28Mhz, with lots of Fast RAM, that I can boot from an SD card and choose which Kickstart version and disk image I want to use. Great. Now what?

Retrobrighting

The problem with old computers’ plastic cases is that they get yellow over time. The plastic used in the 80s and 90s was a mix of ABS and other materials that oxidized and turned yellow when exposed to UV light. The retro enthusiast’s community knows this very well and has come up with a solution for it: retrobrighting.

My Amiga 1000 case wasn’t terribly yellow, but the keyboard was, so I decided to give it a try.

Chemically speaking, retrobright consists of soaking the yellowed plastic in a mix of hydrogen peroxide, a small amount of the “active oxygen” laundry booster TAED as a catalyst, and a source of UV, but there are variants. The 8-Bit Guy has multiple videos covering retrobrighting techniques. If you’re into Reddit, there’s a whole sub dedicated to it.

In my case, I will use this salon hair cream I bought from Amazon. It has a 40-volume volume, which means it contains the 12% peroxide solution recommended for lightening yellowed plastics. Let’s go, then.

As recommended, I start by washing the case and keyboard with soap and water. Then, I dry them and apply the cream. I wrap them in plastic wrap to keep the cream from drying out.

Washed the keyboard keys with water and soap

Washed the keyboard keys with water and soap

Then, I put it under the sun for a day or two, rotating it now and then to ensure an even UV exposure. The result isn’t bad.

My A1000 after retrobrighting

My A1000 after retrobrighting

What works and WDHLoad magic

As I said before, the Amiga 1000 is the first version of Amiga architecture that uses the Original Chip Set OCS. OCS was also the chipset of the A500, A2000, and CDTV. Later, we had the Enhanced Chip Set (ECS) on the Amiga 3000, 500+, and 600 and the Advanced Graphics Architecture (AGA) on the Amiga 1200, 4000, and CD32. If Commodore had survived longer and not been bankrupt, we might have seen a AAA chipset. Wikipedia provides a good comparison of Amiga chip sets.

Although later architectures and chips added better graphical modes with more depth and higher video bandwidth, the main limitation of OCS is its first-generation “thin” 48-pin Agnus, which can only address 512Kb of chip RAM. Since Agnus controls the DMA memory access of the other custom chips, there’s only 512Kb for in-memory, readily accessible graphics, sound, and other essential functions.

This means that the Amiga 1000 can’t run some games and software that require more than that. Some of the most popular Amiga software, games, and demos require at least 1Mb of chip RAM. Or can it?

Here’s the good news. Even though Commodore went bankrupt in the mid-90s, the passionate community of Amiga users continued to grow and develop new hardware and software for the platform. Even today, more than 30 years later, there’s still a thriving community of creative and talented enthusiasts supporting the platform.

One of the most impressive projects still in development today, one that every modern Amiga user knows, is WHDLoad. This tool makes it possible to install software that was originally designed to run only from floppy disks on hard disks. It’s so popular that it became sort of a standard; every single game or demo ever released for the Amiga now has a WHDLoad image.

But the most interesting part of this for Amiga 1000 owners is that WHDLoad comes with lots of features for running the same software on multiple Amiga models with different architectures, and it makes it easy for developers to inject patches and optimizations or modify parts of the original software to behave differently, more efficiently. For example, WHDLoad can switch the Kickstart ROMs during loading, allowing to run games that require Kickstart 1.3 on machines running later versions; it also restores the RAM after the game quits, thus not killing Workbench, and so on.

So, developers started taking advantage of these options and creating highly optimized versions of old software games to run well on WHDLoad and all possible Amiga models. In some cases, they change the code to use fast RAM where chip RAM was used originally, and depending on the case, make the game better, with smoother graphics or a higher frame rate. In other cases, they will give trade-off options. For example, you might be able to run a game that requires 1Mb chip RAM on 512Kb chip RAM if you turn off some graphics, sound effects, or music.

This made it possible to run ECS games that were never intended to run on OCS machines on the Amiga 1000. And it’s amazing. Here’s Pinball Dreams, a game released in 1992, running on the Amiga 1000:

Pinball Dreams running on the Amiga 1000

Pinball Dreams running on the Amiga 1000

Or Alien Breed Tower Assault, a game by Team 17 released specifically for ECS and AGA machines:

Alien Breed Tower Assault running on the Amiga 1000

Alien Breed Tower Assault running on the Amiga 1000

Still, you can only do so much hacking around, and other more demanding games or recent demos really need that extra chip RAM.

I am running Amiga OS 3.1, which is fairly recent. Tools like Directory Opus or Deluxe Paint work great. ProTracker 2.3 works fine, but after loading it, we are left with only ~280Kb of chip RAM, so we can’t load the larger .mod files.

Professional graphics software like Scala will probably not work, but I haven’t tried it yet.

Overall, my setup is very nice, and the huge Amiga software library offers a lot to explore and play with.

Ongoing and future plans

My Amiga 1000 is the only Amiga I’m running now, and it is still a work in progress. I want to keep improving it where I can.

Right now, I’m fiddling with an open-source PlipBox that I bought pre-assembled to connect the Amiga to the Internet. I want to see how far I can get with it.

I got a HID2AMI dongle from Amibay so that I can use USB mice and joysticks; I want to try that.

I also have this Laser-Tank-Mouse PCB that replaces the internal PCB, mechanics, and ball of the old iconic Amiga tank mouse with a modern optical version.

Longer term, though, I have other ideas I’d like to explore when spare time permits:

RGB2HDMI

As you can see in some of the photos in this post, I initially had this Amiga 1000 connected to my good old Commodore 1084S monitor, just the way it was when I was a kid. This is the same monitor I sometimes use for my other old computers, like the C64. However, a bulky CRT not only doesn’t do justice to the Amiga’s graphical capabilities, but it’s also not practical to move around.

So I switched to a Benq 17" BL702A 15KHz compatible VGA monitor (now deprecated, but still popular in the retro computing community) using an Amiga RGB to VGA filtered buffered adapter. That was nice for a while, but still not perfect, some artifacts and vertical bars, problems with some resolutions and the need to constantly adjust offsets.

So now I’m using a cheap GBS-8220 + GBS-Control upscaler with a modern LCD, and it works very well; I love it. I even 3D printed a case for it recently:

GBS-8220 + GBS-Control upscaler

GBS-8220 + GBS-Control upscaler

But… there’s something even better and more elegant. RGB2HDMI is a software that converts RGB video signals from old computers to low-latency pixel-perfect HDMI signals running on a CPLD and a small Raspberry Pi Pico combo. I already use RGB2HDMI adapters for my C64 and C128; they’re perfect. If you haven’t heard about RGB2HDMI, do yourself a favor and check this great video of Ian Bradbury, one of the creators, explaining how it works and the official Github page.

But there’s a problem: RGB2HDMI was designed for 3-bit (8 colors) RGB output, not 12-bit (4096 colors) like the Amiga. However, there are now options to make it work with 12-bit color systems. Specifically, I can build this Amiga 1000 CPLD Adapter that takes the necessary signals from the Denise video chip, syncs them, and feeds them to the onboard Pico running the RGB2HDMI image. No power supply and minimal soldering are required.

The other advantage of the RGB2HDMI compared to the GBS is that I get flicker-free interlace video resolutions.

So yes, this is the way to go. I ordered some PCBs from PCBWay and the BOM from Mouser, and I’m going to give it a shot. It’s also an opportunity to train my SMD soldering skills.

Rejuvenator or GBA1000

At some point, I’d like to explore options to upgrade the Amiga 1000 to use a Fat Agnus with at least 1 MB of chip RAM support. I don’t have many options right now. I would build a Rejuvenator myself, but it’s useless in a PAL Amiga 1000s without the WCS daughterboard.

I could also build a GBA1000 (more info here), which is the modern successor to the Phoenix board. It is a full motherboard replacement that uses the original ECS chips but with many upgrades. This is definitely an interesting project, but it’d mean throwing my board away, which makes me sad, and building an Amiga from scratch, essentially, similar to what I did with the Frankenstein 64, but x10 times harder.

Still pondering.

Future Parceiro versions

The other thing I’m watching is Mr. David Dunklee’s future versions of the Parceiro. The last time we checked in, he hinted at some ideas he has for the Parceiro roadmap, and I was happy to learn that he thinks that adding a Fat PAL Agnus to the A1000 is not impossible and can be done in a relatively non-intrusive way. This would be a much better option than the Rejuvenator or the GBA1000 because not only would I get to keep my original board, but also the Parceiro already has a lot of the upgrades, if not better ones, that the other options provide.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this blog. I’ve been having a lot of fun fixing, improving, and playing with this machine, which I consider a piece of retro computing history. Feel free to reach out if you have questions or comments or want to chat about Amigas; check my contacts page for details. I hang around Bluesky these days. There’s also a Two Stop Bits thread.

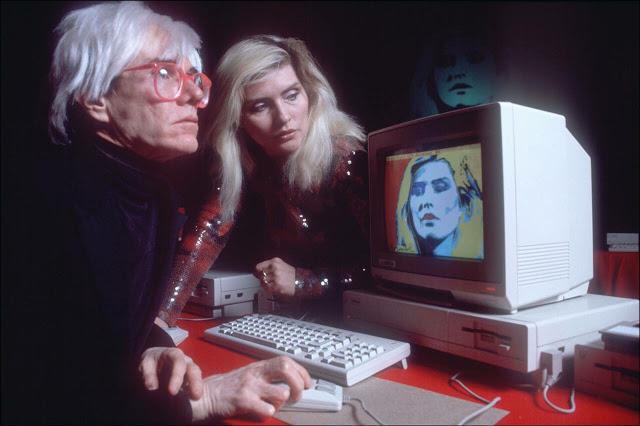

Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry using the Amiga 1000

Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry using the Amiga 1000

NewTek Demo Reel 1

NewTek Demo Reel 1

A Rejuvenator from an Amibay sale

A Rejuvenator from an Amibay sale