The EU Cookie Law is dead

It’s a fact that Facebook and Google (including Youtube) own a sizeable chunk of the global internet traffic and their competitive advantage boils down to two things: computing power and data. These two giants’ core businesses depend exclusively on tracking us to our tiniest move and correlating what they know about us across their products and platforms. And boy, do they know about us.

Eric Schmidt once said, “The Internet is the first thing that humanity has built that humanity doesn’t understand, the largest experiment in anarchy that we have ever had.”.

And so, in 2012 the EU Cookie Law was born.

I’ve always had a pet peeve with the EU Cookie Law and never been shy about it. Since the very first moment after the bill passed and all EU countries began adopting the directive, I knew we were facing an apparently noble idea, but sadly, terribly implemented.

For those of you who don’t know what the Cookie Law is, this website explains:

“The Cookie Law is a piece of privacy legislation that requires websites to get consent from visitors to store or retrieve any information on a computer, smartphone or tablet.

It was designed to protect online privacy, by making consumers aware of how information about them is collected and used online and give them a choice to allow it or not.”

The EU Commission website adds:

“EUROPA websites must follow the Commission’s guidelines on privacy and data protection and inform users that cookies are not being used to gather information unnecessarily.

The ePrivacy directive – more specifically Article 5(3) – requires prior informed consent for storage for access to information stored on a user’s terminal equipment. In other words, you must ask users if they agree to most cookies and similar technologies (e.g. web beacons, Flash cookies, etc.) before the site starts to use them.”

Europe is careful and slow. We like to take our time to think things through before we go on and write our bold decisions on stone, for eternity, sometimes wrong ones. We’re the opposite of what lawmakers and regulators should be if we’re to take the opportunity to innovate, use the fast changing digital revolution and advance our lives for the better: a lean approach, repeating the “make, measure, learn” cycle.

No problem though, I can perfectly live with Europe’s collective ideological beliefs and tendentially conservative policies which are often too late to make a difference, especially in the digital context, but not at the expense of crippling one of humanity’s greatest achievements in recent history, the Internet.

Where do we stand

Four-year have passed since the Cookie Law started back in 2012, so where do we stand?

The web is broken

{: .left }

{: .left }

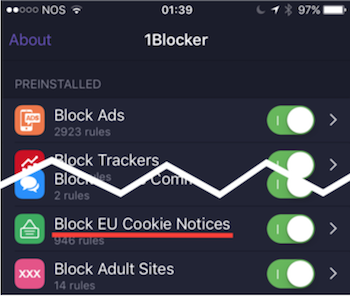

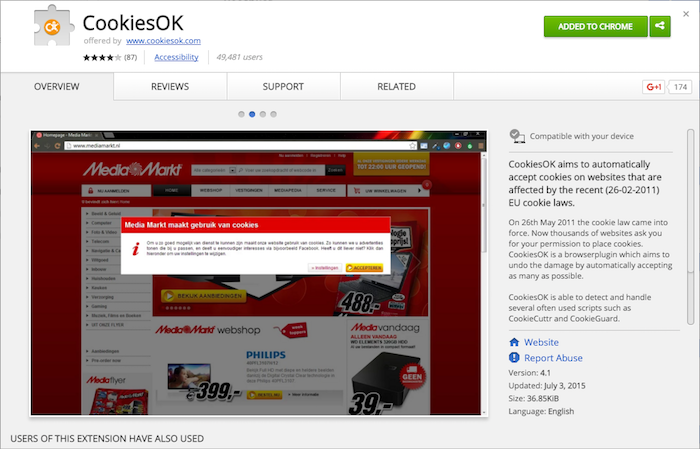

We now have a broken web. Thanks to our bureaucrats in Europe we have developed an involuntary instinct to ignore entirely, tick and click the infamous cookie law notices without reading one single word of what’s in there. It’s gotten so bad that some ad blockers are now classifying the well-intended cookie notices as spam, trash content. Chrome extensions to auto-close the cookie banners are trending too. To make things worse, the banners appear to us in a wide variety of forms, sometimes breaking an otherwise good design and challenging our patience, not to mention overloading the website with more objects.

But humans are skilled when it comes to avoiding inflicted rules. We’ve learned to identify and nuke those nasty intrusive boxes in milliseconds, and we carry on, bravely, into the world of evil trackers.

Cherry on top: those notices use cookies to remember our decision not to bother us again. But they will.

{: .right }

{: .right }

We don’t understand

The average user doesn’t understand cookies not only because they’re a technicality but mainly because in the eyes of this law a “cookie.” is a metaphor for any software artifact that can track someone online. And as we (software developers) know, there are numerous ways to track a user without using HTTP cookies.

There’s still a tremendous lack of understanding from what one’s digital footprint implicates regarding personal privacy. The fact is we’re being tracked by a lot more stuff than we think:

-

Smartphone OSes, their vendors and the apps running on top of having access to its sensors’ data, our location, contacts, camera, microphone, personal data (including passwords);

-

A myriad of connected sensors wherever you go, some of which were paired to your smartphone, are regularly feeding their masters with your behavioral data;

we now have developed an involuntary instinct to ignore entirely, tick and click the infamous cookie law notices without reading one single word of what’s in there

-

It gets worse; Any device with a radio and antenna, GSM, Wifi, NFC or Bluetooth is probably leaking some information about you without your knowledge or permission. You wouldn’t believe the amount of information that goes on handshake protocols just as your radio skims nearby hotspots and base stations, no user action or connection required. I’ll guarantee that if you have a smartphone, then you’re carrying a “cookie” in your pocket;

-

Telecom providers can track you from the minute you authenticate on their network and correlate from there with a zillion other touch points you have with them, from a digital service to a visit to a physical store;

I’m just scratching the surface here of course. The next step will be to use machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies, now widely available and mature enough, and applying computer power to our data; they’ve got plenty, to not only know our history but predict our future. And trust me, it will be scarily accurate.

We don’t care

Generally speaking, it’s hard to accept that nobody cares about digital privacy in a post-Snowden era. This isn’t exactly true for everyone, of course, especially if you’re a digital privacy activist, but I’m willing to bet that the vast majority of the world online population will happily trade their personal data for small digital or real world benefits. Sometimes empty ones, like discounts, access to content or events or free wifi at the airport.

Facebook is the absolute proof of this. We’re considerably aware that they know everything about our lives, who we are, what we like, who are our friends, and (soon) what we will do in the future. We also know that they’re actively monetizing this data by selling it to brands and advertisers, and yet we’re consciously trading all of this for the benefit of social networking with our family, friends and (mostly) strangers, for free.

There are studies abound too. They show us that millennials are not particularly worried about privacy, and those who are, aren’t concerned with government spying, or big corporations monetizing your data (or even sell it) as we would have thought.

To be honest, I don’t think this means youngsters gave up on privacy. I just think it means they know how the internet works better, they are more sophisticated and well informed, and because of that, less afraid of using it. They feel naturally at ease with the Internet, and they willingly take the decision to trade some of their privacy for other advantages.

That fact is that the world has changed, and for some, if not most, it’s hard to keep up.

Moving forward

The EU Cookie Law has failed to create awareness, educate users on online privacy, or force big corporations to become more transparent on how they’re using our data

Bureaucrats, with all due respect, should refrain from making laws when technologies they don’t fully understand are involved. Every time this happens, a costly mistake is bound to follow. Probably one to haunt us for years to come.

If you’re a digital lawmaker and if you’re going to create discussion groups with experts to validate your intention during the process, as you usually do, I was part of one, please make sure they aren’t also bureaucrats, lawyers or legal representatives of the institutions or people who could teach you something about how the internet works. Get advice from pioneers and innovators, leaders who are respected by their peers, not business or government delegates.

Is there a better way to protect our European citizens and create awareness on online privacy? I think so:

-

If you’re concerned about the people who need help with internet privacy, then the best weapons are education and debate, not dumb useless popups on our faces every time we visit a website. Take the subject to schools and educators, sponsor quality documentaries and content, get them to TVs (I hear that’s still a powerful medium) or Youtube, get an excellent and comprehensive website about online privacy and make it collaborative. Remember, in the absence of knowledge, fear kicks in.

-

For some reason if you need to keep the notices up then there’s a much better route too. Instead of driving us nuts by crippling the design and usability of billions of websites by benefiting no one, please get in touch with the browser vendors. They’re only a handful, and I’m sure they’ll be happy to engage in conversations around a much better approach to inform the European users about the dangers of cookies for tracking purposes. In fact, I think Mozilla is already voluntarily taking a shot at “Tracking Protection”.

-

Get involved with standards bodies like the IETF or the W3C. They can help standardizing the worse of things to cause the least of pain. For instance, the HTTP code 451 was recently proposed to address the Internet censorship, such as web pages blocked by governments. I don’t like it, but at least, the user is adequately informed through a standard interface. W3C has the Tracking Preference Expression and Tracking Compliance drafts running too.

The EU Cookie Law not only has failed to create awareness, educate users on online privacy, or force big corporations to become more transparent on how they’re using our data but it’s also not addressing what should concern us.

It’s become a hurdle.